|

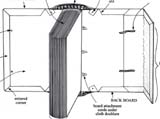

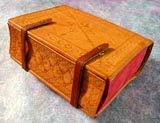

Image of characteristic features of an Armenian binding from Mathews and Wieck ed., p. 133. Image of V-shaped notches on the folded edge of gatherings from Mathews and Wieck ed., p. 131. Image of attachment of text block to boards from Sanjian ed., pl. 31. University of Iowa |

"This holy Gospel is 307 years old." When the Gladzor Gospel came to UCLA the codex was bind in the 19th century lacquered covers. Although the pages of the codex were in good condition, the binding was completely inadequate. The front gatherings were loose and failing apart, while rest of the codex was sewn too tight and it would not lay flat when open. To remedy the situation, the curator of the manuscripts in the UCLA Special Collection decided to disband the book. Collation. The manuscript is made of heavy, brownish vellum and the first gathering is of slightly whiter and finer vellum. The text block of the codex is composed of twenty-four quires, which are gatherings of six bifolia. Ten of the gatherings are regular, while fourteen have some missing leaves or inserted single leaves. The individual leaves are inserted at the initial assembling of the manuscript, and they sometimes carry text and sometimes miniatures. The first and the last page of each gathering have mark of the quire signature in the middle of the lower margin. The first gathering with the Canon Tables, eight and last gathering are all unmarked. The second and ninth gatherings are missing quire signature due to page loss. After unbinding, some gathering and leaves were reordered, to correct changes that occurred during 19th century binding: original first flyleaf was used at the end, the blank page from folio twenty-four was folded so that serve as first flyleaf; some bifolium was mixed up, and two single sheets were inserted at the wrong places. Ruling of the pages. There are no visible rulings or pricking on the pages of the codex. The Armenian scribes used variety of the methods to rule the lines on the page. Besides methods widely known in the Europe, like pricking, the Armenian scribes used also a ruling frame, method that they probably observed from their Islamic counterparts. On the board, the strings were attached in pattern of columns and horizontal lines of the page, parchment or damp paper would be pressed against the frame resulting in pattern of raised ridges in the place of text lines. Ink. Most of the scribes prepared their own ink, but it was not the absolute rule. The scribes in the Gladzor Gospels used a carbon based ink (lampblack), made of soot suspended in a glue or gum Arabic. For difference of iron-gall ink, lampblack gives rich black color and do not chemically react with the vellum. However, exactly because of that quality it also has a strong tendency to flake off. Pigments. For paintings and ornaments, the outlines of drawings were usually marked with a light brown pen or brush. If it was possible, paintings were executed on the rough (hair) side of the parchment. In the Gladzor Gospels, as was the practice in many luxury manuscripts, in gathering with the full page illustrations (especially the Canon Tables), the facing pages of illustrations would be followed with facing pair of blank pages (flash side). A pigment was bind to a parchment with an egg yolk (glair). There are no written recipes for mixing of pigments in the Armenian literature. In the year 1981, Mary Virginia Orna and Thomas F. Mathews performed extensive pigment analysis of the number of Armenian, Persian, Byzantine and Turkish manuscripts. The manuscripts were from a different time periods: from as early as 10th century (Armenian manuscript from the Armenian monastery on island of San Lazzaro near Venice) to as late as 18th century (Turkish manuscript from the Spencer Collection in the New York Public Library). The analysis showed the differences in pigment base (organic vs. mineral) of different manuscript traditions, as well as the differences in pigment mixture between scriptoriums within the same tradition. The analysis confirmed the thesis that the Gladzor Gospels were illustrated in two different scriptoriums, and not just by various artists inside the same scriptorium. While the Byzantine illuminators preferred pigments of the organic base, which decompose over time becoming less intense, the Armenian painters (particularly one following Cilician painting tradition) showed the strong preference for mineral pigments. Besides gold, the Armenian painters of the Cilician tradition used white lead, vermilion, ultramarine, orpiment and red lake. Less often they would use indigo and an organic yellow, both imported from India. Unlike in Islamic color palette, the natural, mineral green do not feature in the Armenian scriptoriums - greenish colors are achieved by mixing orpiment with indigo or ultramarine. The white lead and vermilion (cinnabar) were quite old and well-known pigments. During the Middle Ages ultramarine and azurite was almost exclusively mined in Afghanistan (Badakshan region) and was quite a rare and expensive pigment in Europe. The Armenian painters had much easier access to it and their ultramarine pigments are of very high quality. In the Gladzor Gospels, all painters but the Evangelist Painter (the Second Painter) use ultramarine for their blues. The Evangelist Painter use exclusively azurite. The red lake pigment was prepared from the secretion of laccifer insect which lives in India and Far East. Sometimes the vivid red color was obtained by using pigment extracted from worm known as Armenian vortan, found exclusively in Armenia. Boiling the worm gave a particularly rich red dye (kirmiz), widely used for dying wool and silk employed in Armenian carpet weaving. The pigment mixed with the sealing wax would give the whole range of red tones: from fine pink to the dark violet. However, in the Gladzor Gospels painters rely on the traditional red lake for their magentas and vermilion for their reds. In addition, the Gladzor scriptorium uses a particular mixture of the red lake and ultramarine for their purple, the combination that never occurs in the first scriptorium. For their range of the yellow and orange colors both scriptoriums used a mineral orpiment known from the ancient times for its vivid golden hue. The pigment was naturally occurring around the Lake Van region and easily available. In the Gladzor scriptorium orpiment was sometimes mixed with a yellow organic pigment, known as gamboge, made in part of India and Southeast Asia from gum resin. Binding. The removal of covers from the codex reveled that they are not attached to the text block in the medieval way, but with: "a pair of black leather hinges, which were glued flat on the spine of the book, overlapping in the middle. … Beneath these black hinges two little wedges of cardboard created artificial horizontal ridges, or hubs, across the spine in imitation of the ridges that would be created by the stitching in a medieval binding. On the inside, the hinges of printed cotton cloth connected the covers to the first and last folios of the book. Beneath this artificially constructed spine, the individual gatherings of the book were stitched together with red and green silk thread through four needle holes in the fold of each gathering; all the stitching was then covered with a generous coat of glue to receive the leather flaps of the spine. No evidence remained of earlier bindings of the manuscript except for the stitching holes in V-shaped notches in the fold of each gathering." (Sanjian 1999, p. 48). The Armenian bookbinders, usually monks in a monastery where the manuscript was produced, cut three of four notches (grecquage) in the folding side of gatherings, the number depending on the size of the manuscript. The incisions would sink a tread so that spine was smooth and flat without raised bands characteristic for the European medieval bindings. For the book covers, the Armenian bookbinders would, almost exclusively, use very thin wooden boards, cut with the grain perpendicular to a spine and cut to exact size of the text block. The individual gatherings would be sewn with the herring stitch to a sewing cord, which would then be treaded through the holes in wood and knotted to the boards. The way of sowing, the gatherings differ from tradition of the surrounding cultures, like Greek or Coptic, where the quires would be sown together without support. Another idiosyncrasy of the Armenian bookbinding was use of a guard leaf, parchment page with writing from an old manuscript, which would symbolically connect the newly copied book to the old tradition and reinforce significance of Armenian writing in Armenian culture. The joint between a text block and book covers would be hidden with the cloth doublure. Sometimes the sewing cord would be first looped through the board and then gathering sewn to it, and then the other end knotted to the board. Then, the spine would be covered with a layer of cloth before adding endbands. The endbands on head and tail of spine would be raised above the edges of text block and boards, following the common tradition of the region. The endbands are made from thick primary cord sewn onto the boards and passing through the center of each gathering. The cords were then worked with silk in red, white and black chevron design. Before covering them with leather, the inside of boards would be lined with the cloth doublure to cover the wood and cords. The practice of raised endbands requires that book is stored lying flat instead vertically, side by side on a shelf. The unique feature of the Armenian binding is a fore-edge flap. This leather flap would be lined with the same lining as inners of the boards and glued to the inside of the backboard. Unlike the leather flap of the Islamic binding, the Armenian flap does not fold over the fore-edge into the front board, but covers only the thickness of the text block. Attached to inner side of backboard would be also a pair of leather thongs that are tied or laced to the clasps on the front board, securing the volume from warping. Finished book covers would be worked over with blind tooling in the patterns of the cross or some abstract design, but avoiding the figurative patters or heraldic designs. The cover decoration of gospel volumes would be very similar to the carvings of khachkars, traditional Armenian memorial stones. The front cover would be divided in two sections: a braided cross (Calvary cross) on the stepped pedestal enclosed in a braided frame would be in the upper section; the lower section is covered with dense braided rope pattern. This division symbolizes the theme of the Gospels: Crucifixion (upper panel) and Resurrection (lower panel). A book spine was usually decorated only with thin vertical fillets. The gold tooling was rare, however, for a particularly sacred and valued book [see Book as the Sacred Object] the special silver binding plaques would be made, studded with gems or enamel. The way the Armenian bind their books developed its distinctive features around 12th century and remained almost unchanged until 18th century. Although Armenians were introduced to paper as early as 10th they used vellum for bookmaking up to the seventeenth century. Article about the conservation of 13th century Armenian manuscript Bibliography: Kurdian, H. (1941). Kirmiz. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 61(2), pp. 105-107. Kouymjian, D. (2005). From manuscript to printed book: Armenian bookbinding from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Paper presented at the 2nd International Symposium Printing and Publishing in the Languages and Countries of the middle East, 2-4 November 2005, Paris. Mathews, T.F. and Wieck, R.S. (Ed.). (1994). Treasures in heaven: Armenian illuminated manuscripts. New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library. Orna, M. and Mathews, T.F. (1981). Pigment analysis of the Glajor Gospel book of UCLA. Studies in Conservation, 26(2), pp. 57-72. Sanjian, A.K. (1999). Medieval Armenian manuscripts at the University of California, Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press. Copyright 2006, Vlasta Radan, all rights reserved. |

Codicology

Codicology