TITLE PAGE

INTRODUCTION

GLAGOLITIC PAST

1483 MISSAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

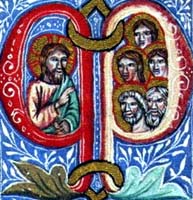

The Missal of Princ Hrvoje, 15th century. One of the most beautifully illuminated Glagolitic missals. The manuscript is in Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul. A selection of digital images from the manuscript is available on the web site of the Insitut of Old-Slavic, Zagreb

Spovid općena, 1496, Senj. Translation of Confessionale generale by Michael de Carcano. The last page with colophon and printer device of Blaž Baromić.

PRITNTING OF

THE GLAGOLITIC BOOKS

The adherence to the Glagolitic tradition required that all books needed for liturgy must be produced locally. All books that could be brought from abroad needed to be first translated and then copied, and that by scribes who were familiar with the Glagolitic tradition. The most common liturgical books in this area are breviaries, a prayer book put together by the Franciscans Third Order and shortened from the Benedictine version to suit their missionary purposes. Some of the coastal monasteries, especially in Vrbnik (island Krk), Zadar, and Dubrovnik, established well organized and productive scriptoria. However, book production could never really satisfy the demand on the field, and the Glagolitic clergy, by choice or necessity, always performed their services with a minimum of books.

The how rare were books among the clergy, could be seen from the edict issued by the Glagolitic bishop of Krk in the year 1457, ordering that every Glagolitic priest must possess at least one breviary. They were given two years to obtain one, by copying or through a trade. Sometimes the parishes would buy the books for their priests, but very often the books were owned by the parish and only loaned to the priest while in service there (Stipčević 2004, pp. 194-195).

To remedy this situation, in the year 1492 Glagolitic bishopy of Senj send the priest Blaž Baromić to Venice to learn the art of printing. He apprenticed in the print shop of Andreas Torresani (1451-1529), where he also assisted in printing a Glagolitic breviary (1493 Breviary). The print shop in Senj published its first book in the 1494 (a missal) and operated until 1508. This print shop was not the first one to print the Glagolitic texts, but it is not clear if the first two titles (1483 Missale Romanum and 1491 Roman Breviary) were printed in Venice or somewhere in continental Croatia (Modruš or Kosinj).

Most of the eight books printed in Senj were translations of various Latin and Italian texts arranged in completely new compilations and being quite ambitious projects. The five of them were translated into a local vernacular (čakavski). In contrast to the Italian vernacular, the Glagolitic script was used very rarely for Croatian secular literature. The coastal notaries used Glagolitic as the script for their official documentations only with the understanding that this was for the benefit of the less educated. That attitude limited Glagolitic writing to the middle class of the rural Croatian speaking population and to lower clergy. However culturally important in retrospective, this association with rural and profane was the reason why Glagolitic never appealed to the Renaissance humanists. They, educated predominantly in Italy, even when writing in the vernacular did so exclusively in Latin script.

With closing of print shop in Senj, all printing activities moved northward, up the coast. In the year 1530, in the town of RIJEKA, the local bishop organized the printing of five liturgical books in the Glagolitic script (Pelc 2002, p. 241). In the year 1531, even that print shop ceased its operation. After disbanding of the print shop in Rijeka, the sporadic printing of Glagolitic books continued in Venice, where were produced some of the most beautiful examples of Glagolitic books (the Glagolitic primer from 1517). However, printing in obscure script and language was always associated with complications and additional costs (special fonts, editors, and proofreaders, problems with distribution). The new technology of printing proffered standardization, and the market as well as the political interest in Glagolitic script was too small to justify the costs.

GLAGOLITIC SCRIPT

GLAGOLITIC SCRIPT

GLAGOLITIC LITURGY

GLAGOLITIC LITURGY

Bibliography

Pelc, M. (2002). Pismo-Knjiga-Slika: Uvod u povijest informacijske kulture. Zagreb: Golden marketing.

Stipčević, A. (2004). Socijalna Povijest Knjige u Hrvata (Knjiga I. Srednji Vijek: Od prvih početaka do glagoljskog prvotiska iz 1483 godine.). Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Written by Vlasta Radan.

Last update April 10, 2006.